Desain Modul Kamera Huawei Mate 40 Pro Bocor Jelang Peluncuran – Huawei terlihat dengan desain…

Gaosudin.com

Recent News

Daihatsu Sigra Kalahkan Honda Brio, Toyota Calya Soal Mesin

Daihatsu Sigra Kalahkan Honda Brio, Toyota Calya Soal Mesin – Kehadiran Toyota Calya 2022 dan…

Tidak Mau Kalah Suzuki Keluarkan Mobil Baru Untuk Bersaing,fortuner Dan Pajero Sport?

Tidak Mau Kalah Suzuki Keluarkan Mobil Baru Untuk Bersaing,fortuner Dan Pajero Sport? – Kali ini…

Instagram Kini Hadirkan Fitur Baru Reels Dan Kamera Depan Belakang

Instagram Kini Hadirkan Fitur Baru Reels Dan Kamera Depan Belakang – Demi kenyamanan pengguna Instagram,…

Inilah Cara Mengkonversi Tv Analog Ke Tv Digital Dengan Stb

Inilah Cara Mengkonversi Tv Analog Ke Tv Digital Dengan Stb – Panduan LENGKAP agar TV…

Wah, Robot Catur Patahkan Jari Anak Saat Turnamen Digelar

Wah, Robot Catur Patahkan Jari Anak Saat Turnamen Digelar – Catur bukanlah permainan kontak fisik,…

Inilah Penyebab Ac Rumah Cepat Bocor Dan Bagaimana Cara Memperbaiki Nya

Inilah Penyebab Ac Rumah Cepat Bocor Dan Bagaimana Cara Memperbaiki Nya – Jika air tiba-tiba…

5 Rekomendasi Terbaik Untuk Penyedot Debu Untuk Menghilangkan Debu!

5 Rekomendasi Terbaik Untuk Penyedot Debu Untuk Menghilangkan Debu! – Membersihkan rumah adalah salah satu…

Yamaha Sekarang Menghadirkan Lagi Teknologi Terbaru

Yamaha Sekarang Menghadirkan Lagi Teknologi Terbaru – JAKARTA, – Yamaha MT series dikenal luas sebagai…

Hyundai Mpv Baru Akan Di Lepas Di Pasaran Cek Harganya Disini

Hyundai Mpv Baru Akan Di Lepas Di Pasaran Cek Harganya Disini – Segmen MPV tujuh…

Suzuki Keluarkan Mobil Baru Sangar, Saingi Fortuner Dan Pajero Sport?

Suzuki Keluarkan Mobil Baru Sangar, Saingi Fortuner Dan Pajero Sport? – Hyundai akan segera memiliki…

Tanggapan Apple Mengenai Kamera Iphone 14 Pro Bergetar

Tanggapan Apple Mengenai Kamera Iphone 14 Pro Bergetar – Apple saat ini sedang bekerja untuk…

Capcut Template New Trend 2022 Habibi

Capcut Template New Trend 2022 Habibi – Tentang Saya Kisah Jihad Fahim Lo Honiara CapCut…

Waspada Berbagai Cara Modus Penipuan Atm Terbaru

Waspada Berbagai Cara Modus Penipuan Atm Terbaru – “Hati-hati teman-teman, saya ingin orang tua tahu…

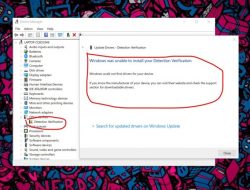

Cara Memperbaiki Driver Audio Pc/ Laptop Yang Error Pada Windows 10

Cara Memperbaiki Driver Audio Pc/ Laptop Yang Error Pada Windows 10 – Ketika kita menggunakan…

Inilah 7 Langkah Sukses dalam Menjalankan Bisnis Baru

gaosudin.com – Bagi banyak orang, memulai bisnis baru adalah pilihan yang menarik. Untuk menjalankan bisnis…

10 Tren Investasi Saham Paling Populer

gaosudin.com – Berinvestasi di saham telah menjadi tren akhir-akhir ini, dan banyak orang yang tertarik…

Inilah Dia Apakah Doji Bisa Digunakan untuk Trading Saham?

gaosudin.com – Apakah Doji Bisa Digunakan untuk Trading Saham? Doji adalah pola candlestick yang biasa digunakan oleh para trader untuk mencari sinyal entry semua instrumen trading termasuk saham. Cara Penggunaan? Analisis teknis adalah metode yang paling banyak digunakan untuk menganalisis pergerakan harga instrumen perdagangan apa pun, mulai dari Forex, Kripto, hingga Saham. Biasanya, trader teknis menggunakan pola kandil untuk mendapatkan wawasan tentang pergerakan harga saham dalam jangka waktu pendek dan panjang. Salah satu pola candlestick yang umum digunakan oleh trader teknikal adalah […]

Berikut 6 Cara Mengatasi Sakit Dada Sebelah Kiri di Rumah

gaosudin.com – 6 Cara Mengatasi Sakit Dada Sebelah Kiri di Rumah. Nyeri dada di sisi kiri sering…

Pelajari Teknik Scalping: Strategi Pendek dalam Trading Forex

gaosudin.com – Teknik scalping adalah strategi trading forex jangka pendek yang populer di kalangan trader….

Ada 3 Cara Mudah Mendapatkan Cashback Trading Di GKInvest

gaosudin.com – 3 Cara Mudah Mendapatkan Cashback Trading Di GKInvest. Selain berdagang secara mandiri dan menghasilkan keuntungan, pedagang juga dapat meningkatkan pendapatannya melalui program perdagangan cashback GKIvest. Lihat cara kerjanya di sini. GKInvest adalah salah satu broker lokal Indonesia dengan reputasi yang tak terbantahkan. Global Kapital Investama Berjangka atau GKInvest berkantor di Jl. Kuningan Mulia, Jakarta, dan legal dari Badan Pengawas Berjangka Komoditi (BAPPEBTI) dengan Izin Usaha Pialang Berjangka No. 01/BAPPEBTI/SP-PN/06/2016 dan Persetujuan Peserta SPA 1218/BAPPEBTI /SP/5/20 […]

Berikut Cara Terbaik Untuk Menginvestasikan Uang Di Tahun 2023

gaosudin.com – Berinvestasi dapat dilihat sebagai peluang menabung untuk cuaca buruk. Mereka membantu Anda mendapatkan…

Tips Cara Diversifikasi Kripto Bagi Pemula

gaosudin.com – Cara Diversifikasi Kripto Bagi Pemula – Mempersiapkan antisipasi risiko sangat penting, terutama saat berinvestasi di aset dengan volatilitas tinggi dan berisiko…

Ini Dia 7 Manfaat Bawang Putih untuk Kesehatan

Bawang putih adalah salah satu bumbu dapur favorit untuk menambah aroma dan rasa pada masakan. Selain sebagai bahan kuliner, bawang putih memiliki banyak manfaat kesehatan lainnya yang berkaitan dengan jantung dan sistem darah. Berbagai manfaat bawang putih untuk kesehatan dapat dikaitkan dengan adanya allicillin, yang bertanggung jawab atas rasa pedas bawang putih. Berikut adalah beberapa manfaat kesehatan yang terbukti dari bawang putih. Baca ulasan lengkap kami jika Anda memiliki pertanyaan. 1. Menurunkan tekanan darah Bawang putih dapat menjadi obat bagi penderita hipertensi, meskipun memiliki […]

Ini Dia 5 Platform Perdagangan Saham Terbaik Untuk Pemula 2022

gaosudin.com – Saya belum pernah menemukan platform untuk membeli dan menjual saham secara online. Saat ini ada lusinan bahkan ratusan platform perdagangan saham yang memungkinkan Anda berdagang saham dengan biaya rendah dan minimum akun. 5 platform perdagangan saham terbaik untuk pemula di tahun 2022. Di sisi lain, ini berarti memilih broker saham online yang sesuai dengan kebutuhan Anda bisa jadi sulit. Dalam panduan ini, kami akan membahas lima platform […]

No More Posts Available.

No more pages to load.